Prostate Cancer

Background

In Canada, prostate cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer among men [1]. Important risk factors for prostate cancer include age and family history, however, little is known about the modifiable risk factors for the disease, including occupational causes. Occupational exposures that affect the endocrine system, such as shift work, are of particular interest given that prostate cancer can be a hormone-sensitive malignancy. Occupational patterns of prostate cancer risk have has been a major area of research for the Occupational Cancer Research Centre [2–5]

Possible occupational risk factors

These work-related exposures are possible risk factors for prostate cancer, but evidence is currently inconclusive.

-

- Metallic compounds (e.g. cadmium, chromium and arsenic) [6,7]

- Exposure to x- and gamma-radiation [6]

- Chemical exposures (e.g. rubber compounds, pesticides such as malathion, and diesel exhaust) [8,9]

- Sedentary behavior/physical inactivity [10,11]

- Work-related psychological stress [12,13]

- Shift work [6]

- Whole body vibration [14]

Key Findings

The greatest risks of prostate cancer were observed among transportation, firefighting, police occupations, and white collar occupations. Pesticide exposure among agricultural workers has been previously explored as a potential prostate cancer risk factor [15]. No excess risk was observed among these workers in the ODSS.

Transportation sector

Employment in transportation industries and occupations was associated with an increased risk of prostate cancer. Possible exposures in these groups include sedentary behavior and physical inactivity, shift work, obesity, and whole body vibration. Exposure to whole body vibration occurs when mechanical energy from vibrating surfaces is passed to the body either in standing or sitting positions. The role of whole body vibrations in prostate cancer etiology remains unclear, but other prostate conditions like prostatitis and increasing testosterone levels have been linked to whole body vibration exposure [14]. Circadian rhythm disruption and cosmic radiation among airline flight personnel has been posited as a potential prostate cancer risk factor [7].

-

- Railway transport operating: 1.36 times the risk

- Railway transport operating support occupations: 1.43 times the risk

- Conductors and brakemen: 1.37 times the risk

- Locomotive engineers and firefighters: 1.32 times the risk

- Air transport operating: 1.15 times the risk

- Air transport operating occupations, nec: 1.29 times the risk

- Motor transport operating: 1.06 times the risk

- Taxi drivers and chauffeurs: 1.42 times the risk

- Bus drivers: 1.16 times the risk

- Truck drivers: 1.05 times the risk

- Other transportation occupations

- Subway and street railway operating occupations: 1.85 times the risk

- Driver-salesmen: 1.25 times the risk

- Transportation industry: 1.07 times the risk

- Urban transit systems: 1.28 times the risk

- Air transport industry: 1.16 times the risk

- Railway transport industry: 1.15 times the risk

- Bus transport, interurban and rural: 1.07 times the risk

- Railway transport operating: 1.36 times the risk

Metal product manufacturing

Elevated risks of prostate cancer were observed for metal-related occupations such as metal processing, metal machining, metal shaping and forming, and metal product fabricating and assembling. These types of jobs may expose workers to elevated levels of possible risk factors for prostate cancer metallic compounds such as cadmium and chromium, which can be components of metal alloys [7,16].

-

- Foremen, metal shaping and forming (except machining): 1.40 times the risk

- Tool and die making occupations: 1.20 times the risk

- Metal forging: 1.19 times the risk

- Moulding, coremaking, and metal casting: 1.17 times the risk

- Welding and flame cutting: 1.12 times the risk

- Primary metal industries: 1.09 times the risk

- Iron and steel mills: 1.13 times the risk

Protective services

Elevated risk of prostate cancer is observed in both firefighters and police. This has been consistently observed in other studies and could be related to shift work, sedentary behaviour, or high levels of occupational stress among these groups [2]. Firefighters may also be exposed to diesel engine exhaust while working in fire halls, which is a potential risk factor for prostate cancer.

-

- Policemen and detectives, government: 1.49 times the risk

- Firefighters: 1.47 times the risk

Healthcare workers

We observed an increased risk of prostate cancer among several occupations in medicine and health, which may be attributable to shiftwork. A possible excess risk has been in relationship to radiation [6]. However, no excess risk was observed among nurses, and there is no conclusive evidence of an association between exposure to ionizing radiation and prostate cancer [7].

-

- Radiological technologists and technicians: 2.40 times the risk

- Medical laboratory technologists and technicians: 1.25 times the risk

- Nursing, therapy and related assisting occupations, not elsewhere classified*: 1.58 times the risk

* This group includes occupations, not elsewhere classified concerned with nursing, therapy and related assisting occupations, including providing supportive services in diagnostic and therapeutic procedures.

White collar occupations

Increased risks of prostate cancer were observed across all management and administrative occupations, as well as in teaching occupations. This may be related to sedentary behavior and low occupational physical activity in white collar work. Additionally, these findings could relate to a greater participation in prostate cancer screening in this group relative to others [17].

-

- Teaching: 1.33 times the risk

- Managerial, administration, and related occupations: 1.20 times the risk

Other findings

Increased prostate cancer risk was observed for certain mechanics and repairers and electrical workers. Potential prostate cancer risk factors are unclear.

-

- Mechanics and repairers except electrical: 1.15 times the risk

- Rail transport equipment mechanics and repairmen: 1.33 times the risk

- Industrial, farm and construction machinery mechanics and repairmen: 1.22 times the risk

- Motor vehicle mechanics and repairmen: 1.14 times the risk

- Electrical power lighting and wire communications equipment, erecting, installing and repairing occupations: 1.19 times the risk

- Electrical power linemen and related occupations: 1.29 times the risk

- Wire communications and related equipment installing and repairing occupations: 1.25 times the risk

- Construction electricians and repairmen: 1.18 times the risk

- Mechanics and repairers except electrical: 1.15 times the risk

Relative Risk by Industry and Occupation

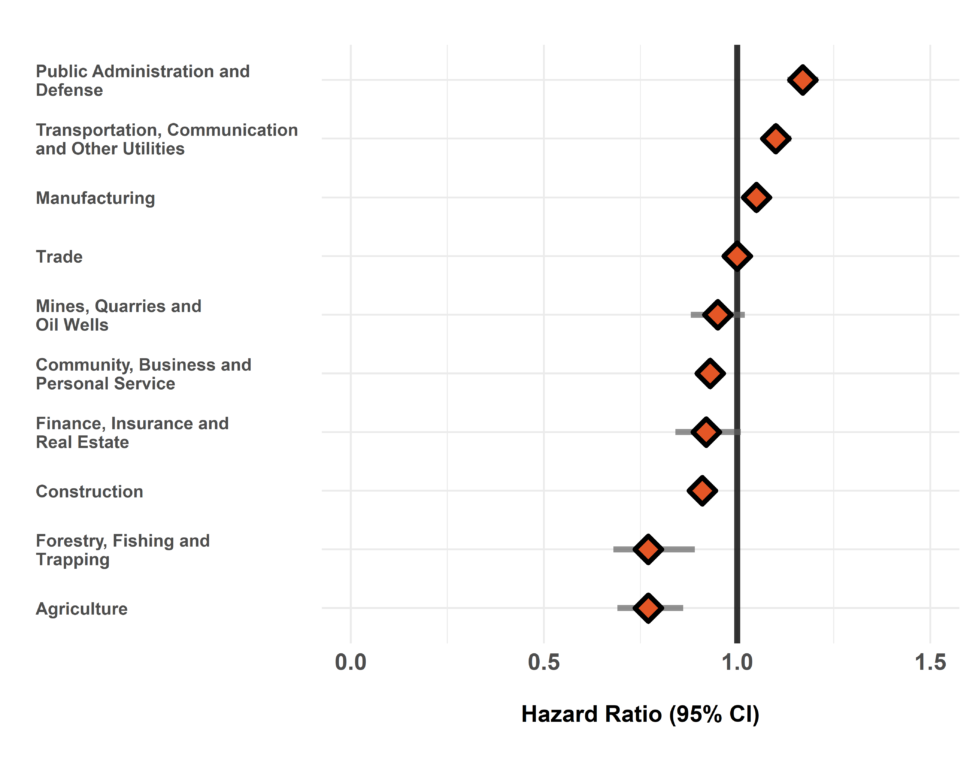

Figure 1. Risk of prostate cancer diagnosis among workers employed in each industry group relative to all others, Occupational Disease Surveillance System (ODSS), 1983-2016

The hazard ratio is an estimate of the average time to diagnosis among workers in each industry/occupation group divided by that in all others during the study period. Hazard ratios above 1.00 indicate a greater risk of disease in a given group compared to all others. Estimates are adjusted for birth year and sex. The width of the 95% Confidence Interval (CI) is based on the number of cases in each group (more cases narrows the interval).

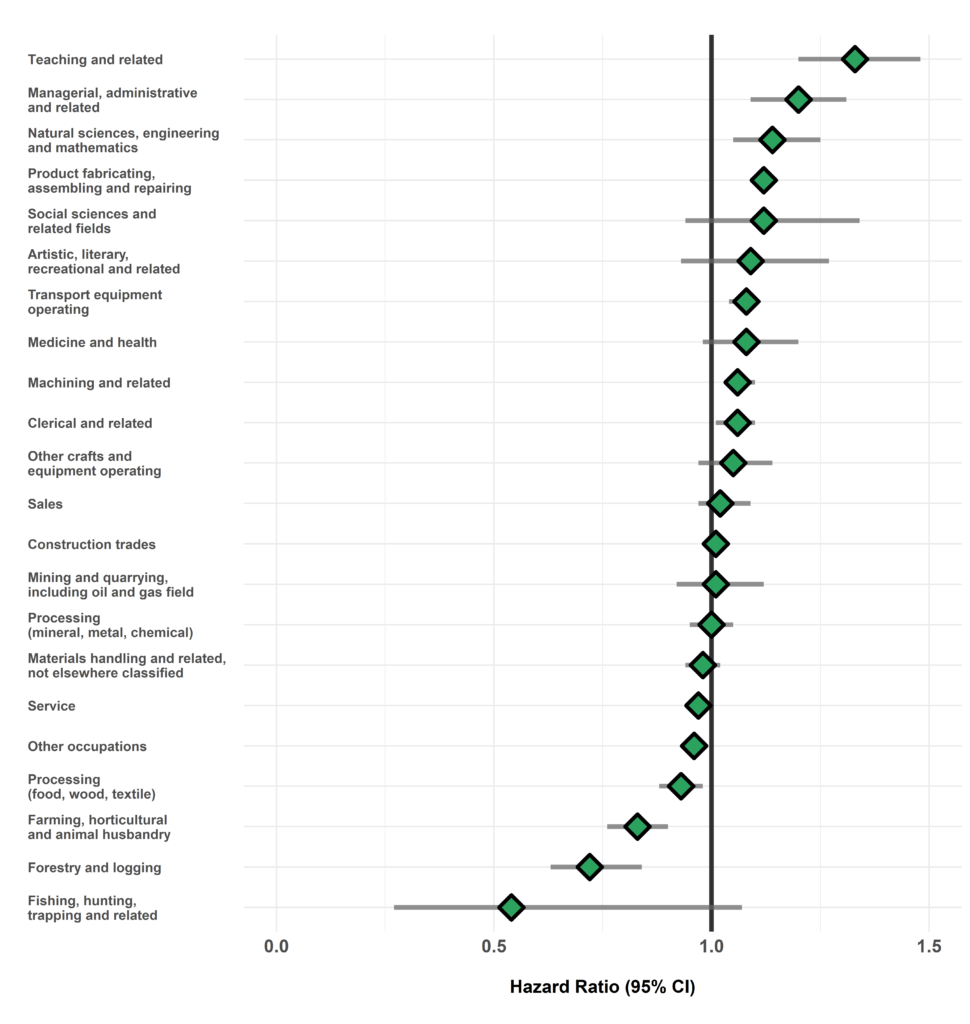

Figure 2. Risk of prostate cancer diagnosis among workers employed in each occupation group relative to all others, Occupational Disease Surveillance System (ODSS), 1983-2016

The hazard ratio is an estimate of the average time to diagnosis among workers in each industry/occupation group divided by that in all others during the study period. Hazard ratios above 1.00 indicate a greater risk of disease in a given group compared to all others. Estimates are adjusted for birth year and sex. The width of the 95% Confidence Interval (CI) is based on the number of cases in each group (more cases narrows the interval).

Table of Results

Table 1. Surveillance of Prostate Cancer: Number of cases, workers employed, and hazard ratios in each industry (SIC)

| SIC Code * | Industry Group | Number of cases | Number of workers employed | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) † |

| 1 | Agriculture | 355 | 26,322 | 0.77 (0.69-0.86) |

| 2/3 | Forestry, Fishing and Trapping |

211 | 10,210 | 0.77 (0.68-0.89) |

| 4 | Mines, Quarries and Oil Wells |

727 | 22,717 | 0.95 (0.88-1.02) |

| 5 | Manufacturing | 13,886 | 528,350 | 1.05 (1.02-1.07) |

| 6 | Construction | 4,036 | 201,737 | 0.91 (0.88-0.94) |

| 7 | Transportation, Communication and Other Utilities |

4,272 | 164,063 | 1.10 (1.07-1.14) |

| 8 | Trade | 5,136 | 290,745 | 1.00 (0.97-1.03) |

| 9 | Finance, Insurance and Real Estate |

416 | 15,213 | 0.92 (0.84-1.01) |

| 10 | Community, Business and Personal Service |

4,583 | 248,947 | 0.93 (0.90-0.96) |

| 11 | Public Administration and Defense |

3,982 | 121,457 | 1.17 (1.13-1.21) |

| * SIC: Standard Industrial Classification (1970) | ||||

| † Hazard rate in each group relative to all others | ||||

Table 2. Surveillance of Prostate Cancer: Number of cases, workers employed, and hazard ratios in each occupation (CCDO) group

| CCDO Code * | Occupation Group | Number of cases | Number of workers employed | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) † |

| 11 | Managerial, administrative and related |

460 | 14,238 | 1.20 (1.09-1.31) |

| 21 | Natural sciences, engineering and mathematics |

533 | 20,819 | 1.14 (1.05-1.25) |

| 23 | Social sciences and related fields |

126 | 6,836 | 1.12 (0.94-1.34) |

| 25 | Religion | <5 | 51 | – |

| 27 | Teaching and related | 351 | 10,033 | 1.33 (1.20-1.48) |

| 31 | Medicine and health | 359 | 17,066 | 1.08 (0.98-1.20) |

| 33 | Artistic, literary, recreational and related |

156 | 8,401 | 1.09 (0.93-1.27) |

| 41 | Clerical and related | 2,103 | 96,268 | 1.06 (1.01-1.10) |

| 51 | Sales | 1,148 | 71,716 | 1.02 (0.97-1.09) |

| 61 | Service | 4,150 | 187,057 | 0.97 (0.94-1.00) |

| 71 | Farming, horticultural and animal husbandry |

573 | 39,144 | 0.83 (0.76-0.90) |

| 73 | Fishing, hunting, trapping and related |

8 | 518 | 0.54 (0.27-1.07) |

| 75 | Forestry and logging | 183 | 10,092 | 0.72 (0.63-0.84) |

| 77 | Mining and quarrying, including oil and gas field |

416 | 12,888 | 1.01 (0.92-1.12) |

| 81 | Processing (mineral, metal, chemical) |

1,384 | 62,806 | 1.00 (0.95-1.05) |

| 82 | Processing (food, wood, textile) |

1,358 | 67,295 | 0.93 (0.88-0.98) |

| 83 | Machining and related | 4,376 | 167,980 | 1.06 (1.03-1.10) |

| 85 | Product fabricating, assembling and repairing |

7,074 | 261,076 | 1.12 (1.09-1.15) |

| 87 | Construction trades | 5,237 | 211,090 | 1.01 (0.98-1.04) |

| 91 | Transport equipment operating |

3,971 | 153,727 | 1.08 (1.04-1.11) |

| 93 | Materials handling and related, not elsewhere classified |

2,365 | 121,849 | 0.98 (0.94-1.02) |

| 95 | Other crafts and equipment operating |

614 | 21,526 | 1.05 (0.97-1.14) |

| 99 | Other occupations not elsewhere classified | 3.503 | 174,480 | 0.96 (0.93-0.99) |

| * CCDO: Canadian Classification Dictionary of Occupations (1971) | ||||

| † Hazard rate in each group relative to all others | ||||

Please note that ODSS results shown here may differ from those previously published or presented. This may occur due to changes in case definitions, methodological approaches, and the ongoing nature of the surveillance cohort.

References

- Prostate cancer statistics – Canadian Cancer Society. [cited 2020 Sep 18].

- Sritharan J, Pahwa M, Demers PA, Harris SA, Cole DC, Parent ME. Prostate cancer in firefighting and police work: A systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies. Environ Heal A Glob Access Sci Source. 2017;16(1):1–12.

- Sritharan J, Macleod JS, McLeod CB, Peter A, Demers PA. Prostate cancer risk by occupation in the occupational disease surveillance system (ODSS) in Ontario, Canada. Heal Promot Chronic Dis Prev Canada. 2019;39(5):178–86.

- Sritharan J, Demers PA, Harris SA, Cole DC, Peters CE, Villeneuve PJ, et al. Occupation and risk of prostate cancer in Canadian men: A case-control study across eight Canadian provinces. Cancer Epidemiol. 2017;48:96–103.

- Sritharan J, Demers PA, Harris SA, Cole DC, Kreiger N, Sass-Kortsak A, et al. Natural resource-based industries and prostate cancer risk in Northeastern Ontario: A case-control study. Occup Environ Med. 2016;73(8):506–11.

- IARC Working Group. List of Classifications by cancer sites with sufficient or limited evidence in humans, Volumes 1 to 113. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC).

- Krstev S, Knutsson A. Occupational Risk Factors for Prostate Cancer: A Meta-analysis. J Cancer Prev. 2019;24(2):91–111.

- IARC Working Group. A Review of Human Carcinogens- Chemical agents and related occupations. Vol. 100F. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC); 2012.

- IARC Working Group. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans- Occupational Exposures in Insecticide Application, and Some Pesticides. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC); 1991.

- Berger FF, Leitzmann MF, Hillreiner A, Sedlmeier AM, Prokopidi-Danisch ME, Burger M, et al. Sedentary behavior and prostate cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Cancer Prev Res. 2019;12(10):675–87.

- Lynch BM, Friedenreich CM, Kopciuk KA, Hollenbeck AR, Moore SC, Matthews CE. Sedentary behavior and prostate cancer risk in the NIH-AARP diet and health study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23(5):882–9.

- Blanc-Lapierre A, Rousseau MC, Parent ME. Perceived workplace stress is associated with an increased risk of prostate cancer before age 65. Front Oncol. 2017;7(NOV).

- Heikkila K, Nyberg ST, Theorell T, Fransson EI, Alfredsson L, Bjorner JB, et al. Work stress and risk of cancer: Meta-analysis of 5700 incident cancer events in 116 000 European men and women. BMJ. 2013;346(7896):1–10.

- Nadalin V, Kreiger N, Parent ME, Salmoni A, Sass-Kortsak A, Siemiatycki J, et al. Prostate cancer and occupational whole-body vibration exposure. Ann Occup Hyg. 2012;56(8):968–74.

- Silva JFS, Mattos IE, Luz LL, Carmo CN, Aydos RD. Exposure to pesticides and prostate cancer: Systematic review of the literature. Rev Environ Health. 2016;31(3):311–27.

- Rapisarda V, Miozzi E, Loreto C, Matera S, Fenga C, Avola R, et al. Cadmium exposure and prostate cancer: Insights, mechanisms and perspectives. Front Biosci – Landmark. 2018;23(9):1687–700.

- Sritharan J, MacLeod J, Harris S, Cole DC, Harris A, Tjepkema M, et al. Prostate cancer surveillance by occupation and industry: the Canadian Census Health and Environment Cohort (CanCHEC). Cancer Med. 2018;7(4):1468–78.