Salivary Gland Cancer

Background

Salivary gland cancer (SGC) is a rare cancer that affects both major and minor salivary glands. The parotid, submandibular, and sublingual major salivary glands are located on each side of the face, and there are hundreds of minor salivary glands located throughout the oral cavity. A majority of SGCs originate in the parotid and the submandibular glands [1]. SGC occurs at an annual rate of 3 cases per 100,000 people [2]. In Ontario, there were 1,222 incident cases and 235 deaths of SGC between 2012 and 2016 [3].

Ionizing radiation is an established risk factor for SGC, particularly during radiotherapy to the head and neck, and during dental or head and neck X-rays [4]. The role of several occupational exposures has also been suggested.

Suspected occupational exposures

-

- X- and Gamma- radiation [5,6]

- Radioiodines, including iodine-131 [5]

- Rubber and plastics manufacturing [6–9]

- Nickel compounds/alloys [6]

Key Findings

Elevated risk of salivary gland cancer was observed among workers in various occupations, with potential exposure to ionizing radiation, nitrosamines, styrene, metal dusts, and several others. As this form of cancer is rare, many groups in the ODSS had a smaller number of cases and results should be interpreted with caution.

Healthcare

Workers in the health care sector are exposed to many known carcinogens such as ionizing radiation from diagnostic imaging and radiation therapy equipment, and formaldehyde [10], which has been associated with increased risk of SGC previously [11]. Nurses, nursing assistants, and orderlies are among the occupation groups with the highest exposure to ionizing radiation [10]. Health care workers may also be exposed to Epstein-Barr virus, which has been linked to SGC [4].

Workers in the health care sector are exposed to many known carcinogens such as ionizing radiation from diagnostic imaging and radiation therapy equipment, and formaldehyde [10], which has been associated with increased risk of SGC previously [11]. Nurses, nursing assistants, and orderlies are among the occupation groups with the highest exposure to ionizing radiation [10]. Health care workers may also be exposed to Epstein-Barr virus, which has been linked to SGC [4].

- Occupations in medicine and health: 1.22 times the risk

- Nurses, registered, graduate and nurses-in-training: 1.54 times the risk

- Nursing assistants: 2.14 times the risk

Rubber and plastics products

Numerous studies have shown rubber and plastic work associated to risk of SGC [6–9]. Elevated risks were observed in the overall industry and specific to plastics fabricating. Exposure to styrene in plastic manufacturing work may be associated with risk of SGC [9]. Rubber workers may be exposed to nitrosamines, which also may increase risk of SGC [6–8].

Numerous studies have shown rubber and plastic work associated to risk of SGC [6–9]. Elevated risks were observed in the overall industry and specific to plastics fabricating. Exposure to styrene in plastic manufacturing work may be associated with risk of SGC [9]. Rubber workers may be exposed to nitrosamines, which also may increase risk of SGC [6–8].

- Rubber and Plastics Products Industries: 1.34 times the risk

- Plastics Fabricating Industry: 1.44 times the risk

- Chemicals, petroleum, rubber, plastic and related materials processing occupations, not elsewhere classified: 1.27 times the risk

Metal-related and mining

Workers in metal-related work may be exposed to nickel alloy dust and chromium VI compounds, which may be linked to risk of SGC [6,13]. Mining and quarrying workers may also be exposed to various metals, as well as other carcinogenic exposures, such as diesel engine exhaust, which may be associated with increased SGC risk [14].

Workers in metal-related work may be exposed to nickel alloy dust and chromium VI compounds, which may be linked to risk of SGC [6,13]. Mining and quarrying workers may also be exposed to various metals, as well as other carcinogenic exposures, such as diesel engine exhaust, which may be associated with increased SGC risk [14].

- Metal Mining Industry: 1.72 times the risk

- Wire and Wire Products Industry: 1.92 times the risk

- Mining and quarrying, including oil and gas field occupations: 1.77 times the risk

- Mining and quarrying: cutting, handling, and loading occupations: 2.16 times the risk

Other groups

Other groups were observed to have excess risks of SGC. Specifically, physical sciences technologists and technicians had the highest increased risk for SGC in the ODSS cohort. This group may be exposed to radioactive material and equipment that emits ionizing radiation. For other groups it is unclear what risk factors may be involved.

- Physical sciences technologists and technicians: 5.80 times the risk

- Policemen and detectives, government: 2.65 times the risk

- Excavating, grading and related occupations: 2.53 times the risk

- Wholesalers of hardware, plumbing, and heating equipment industry: 2.23 times the risk

- Materials handling equipment operators, not elsewhere classified: 2.26 times the risk

- Tellers and cashiers: 2.48 times the risk

- Electronic and related equipment installing and repairing occupations, not elsewhere classified: 2.59 times the risk

Relative Risk by Industry and Occupation

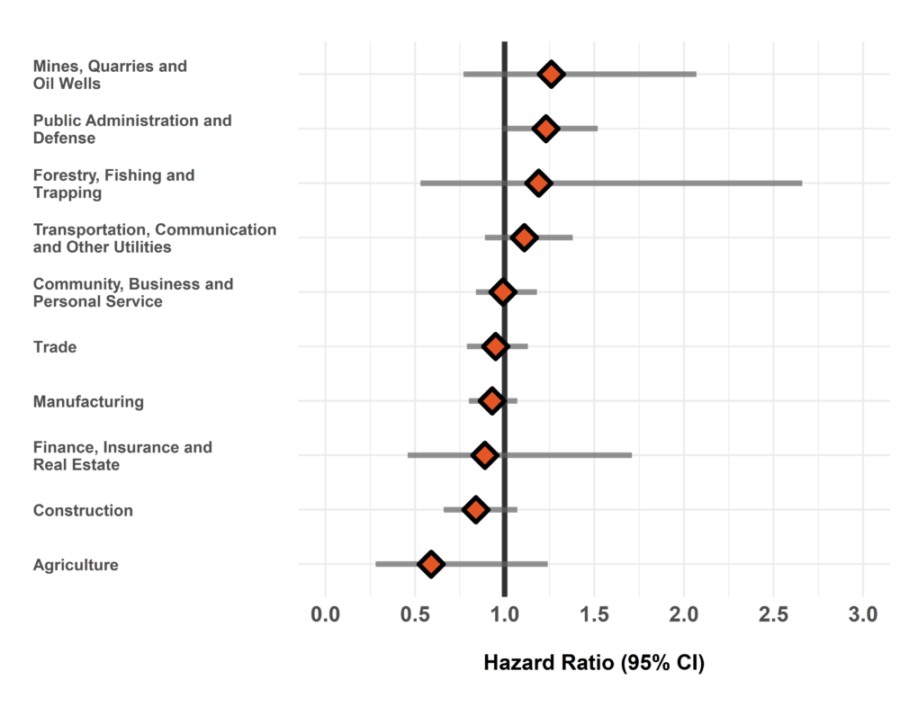

Figure 1. Risk of salivary gland cancer diagnosis among workers employed in each industry group relative to all others, Occupational Disease Surveillance System (ODSS), 1999-2020

The hazard ratio is an estimate of the average time to diagnosis among workers in each industry/occupation group divided by that in all others during the study period. Hazard ratios above 1.00 indicate a greater risk of disease in a given group compared to all others. Estimates are adjusted for birth year and sex. The width of the 95% Confidence Interval (CI) is based on the number of cases in each group (more cases narrows the interval).

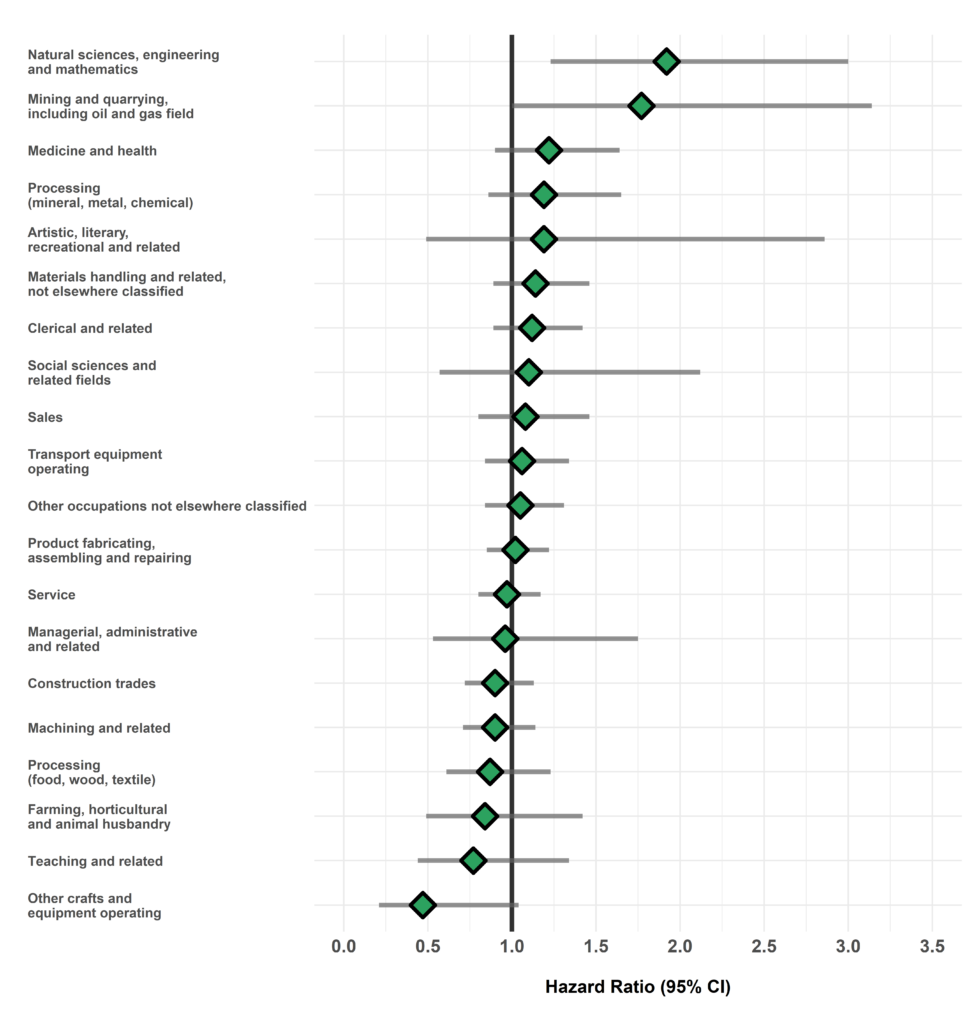

Figure 2. Risk of salivary gland cancer diagnosis among workers employed in each occupation group relative to all others, Occupational Disease Surveillance System (ODSS), 1999-2020

The hazard ratio is an estimate of the average time to diagnosis among workers in each industry/occupation group divided by that in all others during the study period. Hazard ratios above 1.00 indicate a greater risk of disease in a given group compared to all others. Estimates are adjusted for birth year and sex. The width of the 95% Confidence Interval (CI) is based on the number of cases in each group (more cases narrows the interval).

Table of Results

Table 1. Surveillance of Salivary Gland Cancer: Number of cases, workers employed, and hazard ratios in each industry (SIC)

| SIC Code * | Industry Group | Number of cases | Number of workers employed | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) † |

| 1 | Agriculture | 7 | 37911 | 0.59 (0.28-1.24) |

| 2/3 | Forestry, Fishing and Trapping |

6 | 10756 | 1.19 (0.53-2.66) |

| 4 | Mines, Quarries and Oil Wells |

16 | 24919 | 1.26 (0.77-2.07) |

| 5 | Manufacturing | 287 | 717723 | 0.93 (0.80-1.07) |

| 6 | Construction | 75 | 227797 | 0.84 (0.66-1.07) |

| 7 | Transportation, Communication and Other Utilities |

92 | 215032 | 1.11 (0.89-1.38) |

| 8 | Trade | 142 | 469153 | 0.95 (0.79-1.13) |

| 9 | Finance, Insurance and Real Estate |

9 | 26052 | 0.89 (0.46-1.71) |

| 10 | Community, Business and Personal Service |

194 | 669296 | 0.99 (0.84-1.18) |

| 11 | Public Administration and Defense |

95 | 203127 | 1.23 (0.99-1.52) |

| * SIC: Standard Industrial Classification (1970) | ||||

| † Hazard rate in each group relative to all others | ||||

Table 2. Surveillance of Salivary Gland Cancer: Number of cases, workers employed, and hazard ratios in each occupation (CCDO) group

| CCDO Code * | Occupation Group | Number of cases | Number of workers employed | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) † |

| 11 | Managerial, administrative and related |

11 | 37942 | 0.96 (0.53-1.75) |

| 21 | Natural sciences, engineering and mathematics |

20 | 29100 | 1.92 (1.23-3.00)** |

| 23 | Social sciences and related fields |

9 | 35943 | 1.10 (0.57-2.12) |

| 25 | Religion | 0 | 161 | — |

| 27 | Teaching and related | 13 | 61480 | 0.77 (0.44-1.34) |

| 31 | Medicine and health | 50 | 156521 | 1.22 (0.90-1.64) |

| 33 | Artistic, literary, recreational and related |

5 | 18260 | 1.19 (0.49-2.86) |

| 41 | Clerical and related | 78 | 212901 | 1.12 (0.89-1.42) |

| 51 | Sales | 47 | 165047 | 1.08 (0.80-1.46) |

| 61 | Service | 126 | 410169 | 0.97 (0.80-1.17) |

| 71 | Farming, horticultural and animal husbandry |

14 | 55620 | 0.84 (0.49-1.42) |

| 73 | Fishing, hunting, trapping and related |

0 | 599 | — |

| 75 | Forestry and logging | <5 | 10982 | — |

| 77 | Mining and quarrying, including oil and gas field |

12 | 13556 | 1.77 (1.00-3.14)* |

| 81 | Processing (mineral, metal, chemical) |

38 | 82617 | 1.19 (0.86-1.65) |

| 82 | Processing (food, wood, textile) |

33 | 104850 | 0.87 (0.61-1.23) |

| 83 | Machining and related | 77 | 196045 | 0.90 (0.71-1.14) |

| 85 | Product fabricating, assembling and repairing |

147 | 345291 | 1.02 (0.85-1.22) |

| 87 | Construction trades | 88 | 233959 | 0.90 (0.72-1.13) |

| 91 | Transport equipment operating |

79 | 183608 | 1.06 (0.84-1.34) |

| 93 | Materials handling and related, not elsewhere classified |

67 | 162424 | 1.14 (0.89-1.46) |

| 95 | Other crafts and equipment operating |

6 | 29385 | 0.47 (0.21-1.04) |

| 99 | Other occupations not elsewhere classified | 86 | 228161 | 1.05 (0.84-1.31) |

| * CCDO: Canadian Classification Dictionary of Occupations (1971) | ||||

| † Hazard rate in each group relative to all others | ||||

Please note that ODSS results shown here may differ from those previously published or presented. This may occur due to changes in case definitions, methodological approaches, and the ongoing nature of the surveillance cohort.

References

- Adelstein DJ, Koyfman SA, El-Naggar AK, Hanna EY. Biology and management of salivary gland cancers. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2012;22(3):245–53.

- American Cancer Society. Key statistics about salivary gland cancer [Internet]. [cited 2022 Jul 6]. Available from: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/salivary-gland-cancer/about/what-is-key-statistics.html

- Cancer Care Ontario. Burden of rare cancers in Ontario [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2022 May 19]. Available from: https://www.cancercareontario.ca/en/statistical-reports/ontario-cancer-statistics-2020/ch-4-burden-rare-cancers-ontario

- Mayne ST, Morse DE, Winn DM. Cancers of the oral cavity and pharynx. In: Schottenfeld D, Fraumeni JF, editors. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention. Oxford Scholarship Online; 2009. p. 674–96.

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. List of classifications by cancer sites with sufficient or limited evidence in humans, IARC Monographs Volumes 1-131 a Cancer site Carcinogenic agents with sufficient evidence in humans. 2022.

- Horn-Ross PL, Ljung B-M, Morrow M. Environmental factors and the risk of salivary gland cancer. Epidemiology. 1997;8:414–9.

- Mancuso T, Brennan M. Epidemiological considerations of cancer of the gallbladder, bile ducts and salivany glands in the rubber industry. J Occup Med. 1970;12(9):334–41.

- Straif K, Weiland SK, Bungers M, Holthenrich D, Keil U. Exposure to nitrosamines and mortality from salivary gland cancer among rubber workers. Epidemiology. 1999;10(6):786–7.

- Kolstad HA, Juel K, Olsen J, Lynge E. Exposure to styrene and chronic health effects: mortality and incidence of solid cancers in the Danish reinforced plastics industry. Occup Environ Med. 1995;52(5):320–7.

- CAREX Canada. Health care sector report [Internet]. 2019. Available from: https://www.carexcanada.ca/CAREX_Health_Care_Package_Oct_2019.pdf

- Wilson RT, Moore LE, Dosemeci M. Occupational exposures and salivary gland cancer mortality among African American and White workers in the United States. J Occup Environ Med. 2004;46(3):287–97.

- Spitz MR, Sider JG, Newell GR, Batsakis JG. Incidence of salivary gland cancer in the United States relative to ultraviolet radiation exposure. Head Neck Surg. 1988;10(5):305–8.

- Secin I, Uijen MJM, Driessen CML, van Herpen CML, Scheepers PTJ. Case report: two cases of salivary duct carcinoma in workers with a history of chromate exposure. Front Med. 2021;8.

- Swanson GM, Burns PB. Cancers of the salivary gland: workplace risks among women and men. Ann Epidemiol. 1997;7:369–74.